Like father, like son – Camacho Jr. trains with legendary father to prepare for upcoming title fight on ESPN

Even in some of the more impoverished streets of San Juan, Puerto Rico, Hector Camacho Jr. finds signs of encouragement.

A morning jog results in a chance encounter with champions both past and present – Miguel Cotto, Juan Manuel Lopez – all of whom train regularly in their native Puerto Rico, which Camacho Jr. calls “an island for fighters.”

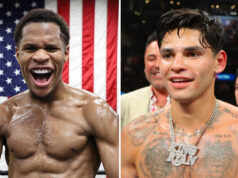

“Every so often you run by them and yell, ‘Keep it up, champ!’ and they acknowledge you back,” said Camacho Jr., who’ll return to the United States later this month to face World Boxing Council U.S. National Boxing Council (WBC USNBC) middleweight champion Elvin Ayala (25-4-1, 11 KOs) of New Haven, Conn., in a 10-round title bout on ESPN2’s “Friday Night Fights” March 30th, 2012 at the Foxwoods Resort Casino’s MGM Grand Theater, presented by Jimmy Burchfield’s Classic Entertainment & Sports.

“We want to see each other win. We back each other. It’s great motivation.”

The son of former four-time world champion Hector “Macho” Camacho Sr., Camacho Jr. (53-4-1, 28 KOs) has spent the past five weeks in Puerto Rico training for what may be the biggest fight of his life – and his first in more than a year since beating Juan Astorga in February of 2011. As an added incentive, he’s working directly with his father, absorbing the knowledge and wisdom of one of boxing’s most electrifying showmen for the first time in his career.

Considering his father, who’ll turn 50 in May, has only been retired for two years, this is one of the few opportunities Camacho Sr. has had to work exclusively with his son without simultaneously having to prepare for one of his own fights. Even though they once fought together on the same show during the latter stages of Senior’s career, this is still the first time the proud father of four has trained his eldest son, quite possibly the highlight of their relationship.

“He’s a great son,” Camacho Sr. said. “I almost cried when he asked me to train him.”

“I wish I had done it sooner,” Camacho Jr. added. “The thing is I trained for years in Puerto Rico with my team. I started off 33-0. Things were going great, and I didn’t think I needed him around. Plus, he had his own career.

“With his life and all of his traveling, we were never on the same page. We finally are now.”

Camacho Sr. has always done things his way – his “Macho World,” as Junior calls it – and he applies that same lifestyle to the manner in which he trains his son.

Senior’s ring exploits, both good and bad, are legendary; in what could be best described as an extravagant career fueled by both unabashed confidence and, at times, prideful stubbornness, Camacho Sr.’s resume includes wins over Roberto Duran and “Sugar” Ray Leonard – the latter which ended Leonard’s career – along with a baffling loss to Greg Haugen in which he lost a point prior to the 12th and final round for refusing to touch gloves with his opponent. Had it not been for the point deduction, the fight would’ve ended in a draw and Camacho Sr. would’ve retained his title.

Even with retirement setting in, Senior remains as fiery as ever, pushing his son to the limit with a style Junior refers to as “tough love” mixed with some of the “Macho” flair that led his father to 79 victories and four world titles.

“He’s always cursing at me and screaming at me; I’m not used to it, but I like it,” Camacho Jr. said. “I’m seeing things start to pan out. He’s on my ass everyday. ‘I did this when I trained!’ or, ‘Why are you running six miles? I ran 10!’ At times, he’ll come off as rude. He’ll yell, ‘Move your fat ass!’ Hey, it works.

“He pushes me. He incorporates some of his old-school training into my training regimen. The work is harder, but I’m seeing the results. As a veteran, there are shortcuts you can take [in camp], but there aren’t any this time – not with my father.”

“He’s sharp,” Camacho Sr. added. “As long as he listens, I won’t get mad at him.”

Though he promises fight fans will see a little bit of his father in him on March 30th, Camacho Jr. won’t change his style completely, not with 53 wins and 28 knockouts under his belt. This is part of the delicate balance he’s dealt with his entire career, constantly weighing the pros and cons of being the son of a living legend. If anything, working with his father has helped Camacho Jr. unwind.

“You’ll see a looser Camacho Jr., that I can tell you,” he said. “My whole approach, my attitude – I feel relaxed. I feel like I’m the more experienced fighter, the bigger puncher, the better fighter; these last six weeks with my father have made a difference.

“I have an edge now.”

While he’s not as flamboyant as his father, Camacho Jr. is still a marketable fighter with the ability to draw crowds and make fans with his respectful attitude and positive energy. In the ring, he’s what Ayala describes as an “agile” fighter who “knows a lot of tricks.”

“He’s very fast,” Ayala said. “He moves a lot. I’ve been working on throwing a lot more punches. Instead of the usual one shot here, and another shot there, I’m adding to my repertoire based on the type of fighter Hector is.”

Ultimately, Camacho Jr.’s goal is to carve his own niche independent of what his father accomplished, a theme prevalent throughout his training camp and supported wholeheartedly by his father, who constantly reminds Junior to “be yourself.”

“Hector always wants to prove that he can be as good or as big as his father,” Camacho Sr. said. “I’ve always told him there’s no comparison. In my time, it was ‘Macho’ time. Now it’s ‘Junior’ time. You just have to be the best you can be by being yourself. If you can’t be the best by being yourself, something’s wrong with you.

“In his own mind, he’s a winner,” he added. “He should be able to go out there and outclass [Ayala] with his boxing ability. I think he’s going to be powerful.”

The 10-round main event on March 30th features features Philadelphia’s “Hammerin’” Hank Lundy (21-1-1, 11 KOs) – ranked No. 4 in the WBC – defending his North American Boxing Federation (NABF) lightweight title against No. 11-ranked Dannie Williams (21-1, 17 KOs), the NABF’s No. 1 contender.