5 Boxers Who Get a Bad Rap but Don’t Deserve It

For many reasons, certain fighters end up being considered “jokes.” Many things contribute to this phenomenon. Things like underserved success, being overhyped, or having things come easy is step one. Then they hit a wall and everyone feels justified for their beliefs. Many times, the general consensus goes overboard—relegating these fighters to the scrap heap of mediocrity.

Sometimes, fighters are prisoners of their own identity, victims of other people’s ideas and prejudices. Being the son of a great fighter or an otherwise overhyped product has its advantages, but often at the expense of overall respect. Sure, these guys cruise on a nicely paved road, while others brave choppy terrain, but it comes at a price. Skepticism becomes heightened. Higher standards come into play. Soon, these guys find themselves trying to live up to a level they were never really capable of obtaining.

It doesn’t mean they weren’t good fighters, though. Here is top 5 list of boxers who have a lot of negativity associated with their careers, including for the above cited reasons, but who were actually pretty good fighters and got a bad rap:

Marvis Frazier

Bear with me please. A guy best known for getting bombed out by Larry Holmes and Mike Tyson, both in the first round, was actually a pretty good fighter. It seems like he’s now merely regarded as a guy who benefited from his father’s fame, parlaying it into a couple quick paydays before fading into the sunset.

While no world-beater, Frazier’s accomplishments were many. He was a top amateur heavyweight, winning National Golden Gloves honors in 1979. Keeping in mind that he would be a cruiserweight today, the smallish Frazier knocked out 21-1 future steppingstone-extraordinaire Steve Zouski in his 4th fight, before racking up some pretty impressive wins. Avenging a defeat from the 1980 Olympic Trials, Frazier beat undefeated prospect James Broad in 1983, following that with a tidy win over perennial contender Joe Bugner. Both were on winning streaks and outweighed Frazier by over 30 pounds.

The beating at the hands of Holmes was embarrassing, with Holmes asking the ref to stop it as he rained right hand bombs on poor Marvis. He seemed like a boy facing a man falling in the first round against a guy not known for early knockouts. It was an imagistic moment of failure that is difficult to forget. Nevertheless, it is surprising and a bit overlooked how well Frazier rebounded from that. In late-1984, he easily beat Bernard Benton by decision. Benton would be a cruiserweight champion within a year.

Then came a trio of excellent victories that perhaps puts a different light on Frazier. In succession, he defeated James “Quick” Tillis, Jose Ribalta, and James “Bonecrusher” Smith—all legitimate contenders with a lot of good fighting ahead of them. Looking at how Tyson performed against those same 3 boxers, Frazier’s work doesn’t look quite so bad.

While Tyson’s 30-second wipeout of Frazier was emphatic and made Marvis look bad, he wasn’t the pitiful figure some now make him out to be. He may have failed miserably against the very best. He shouldn’t have fought at heavyweight. His father trying to make him into a cheap facsimile of himself didn’t help, either. But at the end of the day, Marvis, 19-2 (8 KOs), was indeed a talented fighter.

Gerry Cooney

When Holmes fought Gerry Cooney for the heavyweight title in 1982, it was the last time when race was overtly used as a promotional tool on such a flagrant level. As we now are aware, Cooney came up short and unfortunately for him, no one had much use for a failed “Great White Hope.” Following the Holmes loss, Cooney became some kind of poster boy for failed heavyweight hype-jobs. Maybe it was the white hope thing, his oafish body, his looks, or some other indefinable quality. But when people saw Cooney, their first reaction was usually a condescending chuckle.

Perhaps some of these feelings were warranted after he was poleaxed by George Foreman years later, but the criticism he endured following the loss to Holmes was brutal. Holmes was one of the very top heavyweight boxers to ever walk the earth. If you could isolate his prime into one fight, the Cooney match would at least be a good candidate.

For a 25-year old awkwardly-built Irish guy from Long Island to give Holmes one of his stiffest challenges is a boxing achievement most of us can only dream of accomplishing. Larry himself will attest to the prodigious power and grit of Cooney. For Gentleman Gerry to catch so much heat and mockery for not winning that fight represents one of the more egregious examples of negative “spin” ever perpetrated by fans and media.

Getting blown out by the much-smaller Michael Spinks and aged George Foreman didn’t help his image, but he was well-spent by that time. The backlash from the Holmes fight really destroyed his confidence and therefore his effectiveness as a fighter. But he was good enough to lay out Ron Lyle and Ken Norton in one round apiece. Sure, they were past their best, but the Norton win in particular was something to behold.

In the early-80’s, he might have been the second-best heavyweight in the world. His left hook was one of the more devastating punches in the sport. He may have been a self-destructive guy who profited from being white and failed in his biggest moments, but that doesn’t mean he wasn’t a good fighter.

Mark Breland

When you’re billed as the next Tommy Hearns, just with a better chin, it’s easy to fall short of expectations. It was difficult to not get excited about Breland, with his engaging personality and storied 110-1 amateur career that many said was the best ever. But he didn’t have the electricity of Hearns, which made it hard to get behind a welterweight with heavyweight dimensions beating guys half-a-foot shorter.

His results at first were fine, but he seemed averse to fighting the best, winning a vacant belt against old former contender Harold Volbrecht. By 1987, Marlon Starling was considered an afterthought, a solid fighter, but hardly a threat to the towering Breland. After knocking him out in the 11th round, it was obvious Starling was a diamond-in-the-rough all along, but it didn’t stop people from jumping ship on Breland.

Following a controversial draw in the rematch with Starling, Breland rebuilt nicely, culminating in another victory over an unqualified foe for the vacant WBA belt—a first-round knockout of Korean Seung-Soon Lee. He made 4 defenses before falling to Aaron Davis, who was a hair from being stopped himself. To Breland’s credit, however, he won all 5 of his title fights in his second reign by knockout in 5 rounds or less, including a decisive 3rd-round stoppage of former champ Lloyd Honeyghan. Truth be told, Honeyghan didn’t look like the same guy who had reigned just a few years before.

Some of us may have expected more from Breland. It’s just that the overall negative feeling in the sport about his career is somewhat unjustified. First of all, is there anything wrong with just being a great amateur boxer? His mojo didn’t translate as well to the pro game, but to say his career was a failure is overstating the case quite a bit. He earned every amateur honor available and was one of the top 2-3 welterweights for several years during a underrated era.

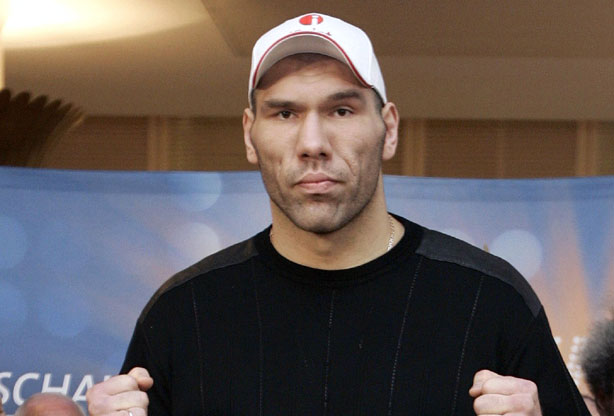

Nikolai Valuev

There are quite a few things that are easy to not like about the guy. A heavyweight who is over 7-feet and 300 pounds who fights like a wuss is not easy to embrace. Couple that with body hair that would make George “The Animal” Steele wince and you got a guy who is difficult to get behind. He’s now looked at as a joke, an aberration that benefited from a weak heavyweight division and an apparently favorable relationship with the WBA.

But unless I’m mistaken, there are a lot of 7-footers who have tried pro boxing. If it were so easy, why did so many fail where Valuev succeeded? He’s not easy to watch, but is it right to look at him as a laughingstock? With wins over Attila Levin, Clifford Etienne, Larry Donald, John Ruiz (twice), Monte Barrett, Jameel McCline, Sergei Liakhovich, and Evander Holyfield, it is clear that he is fact not a bum. Sure, he seemed lucky to get the win over an aged Holyfield. Some of those other fights were also close. He caught a few breaks.

At the same time, those who can say with any certainty that they knew David Haye would be announced the winner after he fought Valuev are not being terribly forthright. He in fact managed to give Haye a close fight that could have gone either way. Considering that Haye was good enough to warrant his fight with Klitschko being hailed as the most important heavyweight fight in years, Valuev’s performance against “Hayemaker” doesn’t seem so awful perhaps.

He might be an oaf. His thirst for combat is also sorely lacking. But if it were so easy for a man his size to have a lucrative pro career while beating several leading heavyweights, then why is he the only giant-sized fighter to ever succeed? The angst projected against him is understandable. But to look at him like he’s a mockery who only succeeded because of his size is not a terribly accurate depiction. Granted, if he were 6’3” and 230 pounds, you wouldn’t know his name. But the history of the sport is replete with freakishly tall fighters, and as of now, Valuev is the only one who ever made anything of it. That should be worth something. Admiration? That might be pushing it. How about some begrudging respect?

Oliver McCall

There are many good things to say about McCall. He could hit like a truck, his chin was absolutely amazing, and boy, could he fight. But when you’re a longtime cocaine addict who has a panic attack in the middle of a big championship fight—it’s not going to bode well for your image. McCall is one of the biggest wasted talents in heavyweight history. He also managed to compile an impressive resume, even more eye opening considering that he was effectively blacklisted from the heavyweight bigtime following the breakdown against Lewis.

The “Atomic Bull” is now 46 and still active in a pro career that began back in 1985. Early on, he developed a reputation as a dependable sparring partner, able to take endless pounding from ferocious fighting forces like Mike Tyson. The 80’s were an apprenticeship period for McCall, who began coming into his own as the 90’s began. A 1991 9th-round stoppage of undefeated and ballyhooed prospect Bruce Seldon signaled his arrival into the upper heavyweight ranks.

A close loss to Tony Tucker in 1992 slowed him a bit, before he crushed talented Francesco Damiani, which set up a WBC title fight against undefeated Lennox Lewis. McCall scored an almost-unfathomable upset, stopping the Hall of Famer in the second round. It was a great win and should go down as such. A decision over a still-useful Larry Holmes followed, before McCall recaptured his underachieving form—dropping a decision and his belt to Frank Bruno.

Still, McCall looked awesome in crushing future titlist Oleg Maskaev in the first round, before falling apart against Lewis. It was one of the more difficult performances to watch, as a drug-troubled McCall began sobbing in the middle of the fight, leading to a TKO loss that left everyone stunned and searching for answers. McCall was a sick man with real problems, but it didn’t stop anyone from relegating him to the scrap heap following this bizarre showing.

Following the Lewis rematch, McCall didn’t lose for another 7 years, but the damage was done and no one was going to risk putting him into another big fight. Since the Lewis debacle, McCall has scored some decent wins—including a knockout of 40-1-1 Henry Akinwande. Since 2006, he has actually had somewhat of late-career revival, beating dangerous Yanqui Diaz and Sinan Samil Sam. In 2009, he beat now-streaking contender Franklin Lawrence and Lance Whitaker. Last year, he beat Fres Oquendo. Even though he dropped his last fight to tough Cedric Boswell, he has shown that he can handle top-20-type opposition, even with over a quarter-century of pro fighting under his belt.

It makes you wonder what could have been if he had stayed clean or lost to Lennox in a more conventional fashion. Those two things really hampered his career, but it still was not a total loss. If he had the internal make-up of an Evander Holyfield, for example, he’d be in Canastota. As it is, he still had a remarkable career. He might be source of mockery, but McCall was no joke.