Examining the Problems with the United States Boxing Team

Even if London 2012 ends with the Team USA not winning a single medal, in my mind it won’t be as bad as Beijing. In 2008, the American boxing squad stank up the joint, losing several fights they should have won easily. This summer, American boxers were bedeviled by draws that consistently pitted them against the strongest opponents around in either the Round of 32 or Round of 16.

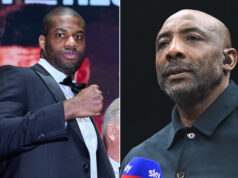

Yet even if this year’s disappointing showing is more explainable than what happened four years ago, it is still a sign of American amateur boxing hitting rock bottom. In Beijing, Deontay Wilder was lucky to pull out a bronze and forestall complete humiliation. In London, Errol Spence must now survive his quarter-finals clash with Russian Andrey Zamkovoy, a tough fight to say the least, just to get to the semi-finals and a matching, face-saving bronze. Asking what is wrong with Team USA is a fair question.

Americans Staying at Home?

The United States has only gradually declined from fielding the strongest boxing team at the Olympics, but the decline is nonetheless clear. We have won only three golds in the last twenty years: Oscar de la Hoya (1992); David Reid (1996); and Andre Ward (2004). The overall medal count has slumped in tandem. Ward had only one fellow teammate reach the podium, Andre Dirrell. The last time the American team looked truly strong was 1996, where we brought home a bucketful of bronze medals (including those won by Floyd Mayweather, Jr. and Antonio Tarver).

The United States has only gradually declined from fielding the strongest boxing team at the Olympics, but the decline is nonetheless clear. We have won only three golds in the last twenty years: Oscar de la Hoya (1992); David Reid (1996); and Andre Ward (2004). The overall medal count has slumped in tandem. Ward had only one fellow teammate reach the podium, Andre Dirrell. The last time the American team looked truly strong was 1996, where we brought home a bucketful of bronze medals (including those won by Floyd Mayweather, Jr. and Antonio Tarver).

There was a time when America’s struggling performance was attributable to a stay-at-home attitude. Decades ago, when Olympic boxing was a different game with very different rules and the United States had a deep, wide pool of pugilistic talent, there was no need for American amateurs to travel to international tournaments. As recently as the 1980s, odds were good that you could see two or three of the best five in any given weight division at the National Golden Gloves or the US Amateur Championship. That world no longer exists.

In absolute terms, American boxing no longer draws the same talent into it as it used to. In relative terms, foreign amateur boxing programs have gotten better. As with so many other things, Americans are not quite as able as they once were, and at a time when the competition has gotten stiffer.

The complaint used to be that because Americans didn’t travel to international tournaments, they missed out on valuable experience and paid for it when they went to the Olympics. That might have been true once upon a time, but not in 2012. A quick look at the resumes of Team USA reveals plenty of fighters who have traveled to the Worlds and other international tournaments. It also reveals that their experiences at those international tournaments was predictive for what happened in London.

The bottom line is that American boxers not being as talented as they used to be may or may not be part of the problem. Lack of international experience is most definitely not.

Is It the Scoring, Or Do We Really Suck?

Part of the blame must be laid at feet of the current Olympic scoring system, a computerized system adopted in response to the infamous robbery of Roy Jones in Seoul’s 1988 games. As I have noted many times in the past, this is a system that rewards straight punches to the head, since those are the punches most likely to be seen by the judges. Barring a knockout, all other aspects of the game (defense, power, ring generalship, etc.) matter only insofar as they influence landing those highly visible punches. The inadequacies of this system are already well-known, and AIBA wants to move to a 10-point must system, similar to that used in professional boxing.

Anyone who has ever trained in both an American and a European boxing gym (and I have) automatically recognizes the significance of the Olympic scoring system, and how it plays out in practice. Whereas American gyms teach primarily to produce pro fighters, boxing in most foreign countries is designed to feed the national amateur circuit. This is why legions of European and Asian boxers pursue “amateur careers” lasting more than a decade, and never express any interest in turning pro, as well as why so many sterling international amateur boxers have problems making the transition to pro boxing.

What my own hands-on experience taught me some time ago is that an American boxer, with a pros-oriented style, needs to be made of excellent stuff to excel at the Olympics, where the scoring system works against him and he must inevitably fight guys who have tailored everything they do to that scoring system.

I still say there is more wrong than just the scoring system. This is the third Olympics for Rau’shee Warren, so if any American has an Olympics-oriented style it must be him, and yet he lost his first match in all three Olympic appearances. If AIBA adopts the pro-style 10-point must system, I expect American boxers to do better. However, it will take more than that to do as well as we used to in Olympic boxing.